by James Corbett at corbettreport.com

(h/t and thx to Urban Pepper)

https://youtu.be/JtOmnZdVFQM

I’m not sure how to break this to you, but it appears the world is ending this weekend. Or at least that’s what you’d believe if you were reading certain corners of the internet.

As you may have already heard, the UN is “taking over the internet” this weekend. But as you’ve also heard if you follow The Corbett Report, that is a complete misrepresentation of what is really happening. Worse, hyperbole about a “UN takeover” of the internet obscures the real solution to ICANN and the centralized DNS system.

But there’s another “end-of-the-world” event taking place this weekend that you might not have picked up on: the SDR.

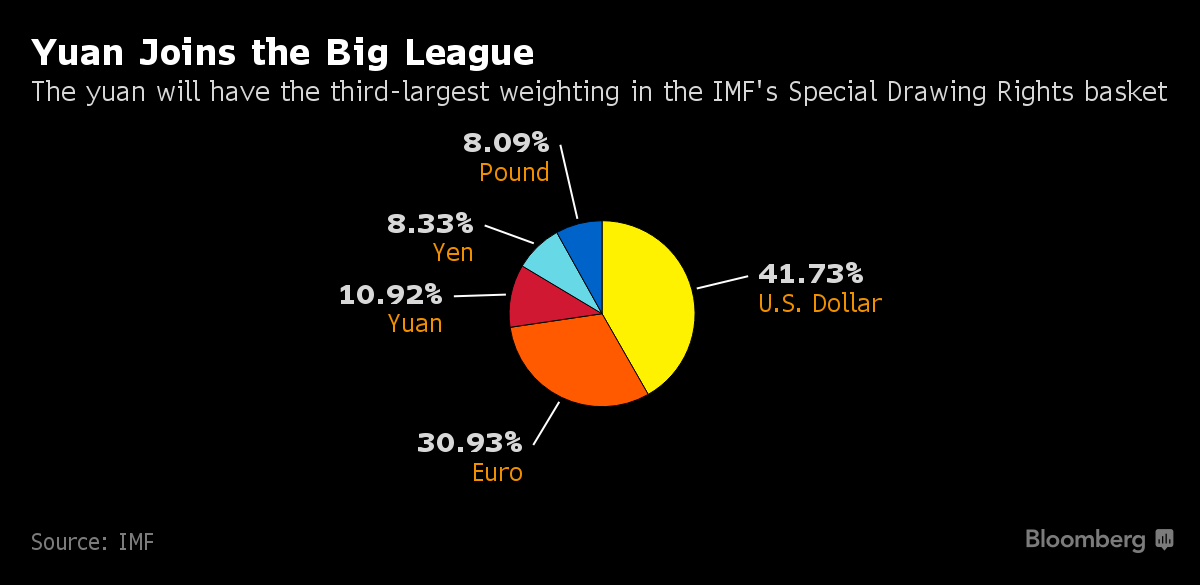

That’s right, the IMF is formally adding the Chinese renminbi (aka the yuan) to their “Special Drawing Rights” basket on Saturday, October 1st. The move boosts the yuan to the status of global reserve currency alongside its basketmates, the pound, the euro, the yen and the dollar. At 10.92% it will be the third highest-weighted currency in the basket, behind the euro at 30.93% and the dollar at 41.73%.

That’s right, the IMF is formally adding the Chinese renminbi (aka the yuan) to their “Special Drawing Rights” basket on Saturday, October 1st. The move boosts the yuan to the status of global reserve currency alongside its basketmates, the pound, the euro, the yen and the dollar. At 10.92% it will be the third highest-weighted currency in the basket, behind the euro at 30.93% and the dollar at 41.73%.

For those who missed my previous reporting on the SDR and the significance of the yuan’s inclusion, here’s the primer:

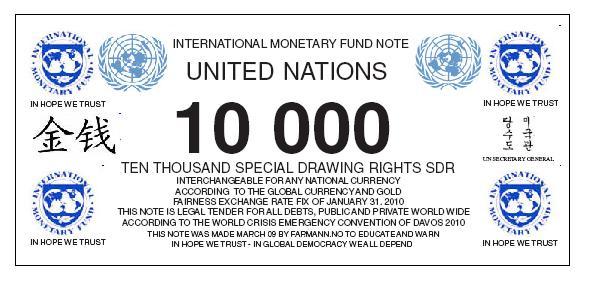

- The SDR is not a currency, but a potential claim on dollars, yen, euros, pounds, and now yuan.

- It is issued by the IMF and held (and traded) as a “supplementary reserve asset” by central banks.

- There are 204 billion SDRs outstanding, equivalent to $285 billion or about 2.5% of total global reserves.

The upshot of the SDR is that it provides liquidity for global transaction settlement in times when dollars and gold are in scarce supply. Inclusion of a currency in the SDR basket means that there is a built-in demand for that currency as central banks tend to match their currency holdings to the basket’s weighting, meaning that central bankers around the world are now (or have already) adjusted their aggregate holdings of yuan to about 10.92% of their portfolio. With $11.6 trillion of reserves globally, that equates to over $1 trillion worth of yuan being held in central bank coffers around the world.

More than that, the move is expected to boost investment in the yuan from both FX reserve managers and global portfolio managers. The FX inflows alone have been estimated at as much as $3 trillion in the coming years, with onshore bond buying accounting for a further $1 trillion of expected foreign investment.

Some outlets are hailing this as the largest transformation of the global monetary order since WWII.

Others, like Barron’s Chi Lo, are putting a wet blanket on that hyperbole. In an article titled “What Now for China as Renminbi Joins SDR?” Lo argues that much of the re-balancing of global reserve portfolios have already been completed, and would have only amounted to an extra $31 billion of demand for the yuan, a drop in the bucket of global liquidity. And global investors, he says, will not base their investment decisions on China’s SDR status, but on China’s commitment to the structural reforms which have been put on the back burner since the yuan achieved SDR status:

Others, like Barron’s Chi Lo, are putting a wet blanket on that hyperbole. In an article titled “What Now for China as Renminbi Joins SDR?” Lo argues that much of the re-balancing of global reserve portfolios have already been completed, and would have only amounted to an extra $31 billion of demand for the yuan, a drop in the bucket of global liquidity. And global investors, he says, will not base their investment decisions on China’s SDR status, but on China’s commitment to the structural reforms which have been put on the back burner since the yuan achieved SDR status:

“SDR inclusion of the renminbi is not relevant to the portfolio re-balancing decision (to increase the weighting of renminbi-denominated assets) of international investors. The impact on global portfolio decisions will come from foreign investors’ assessment of China’s fundamental outlook, the opening of China’s capital account and the decision by international index providers, such as MSCI, to include Chinese A-shares in their global indices.”

So who’s right? Is this the dawn of a new monetary order, or a blip of little significance in and of itself? Well, in a weird way perhaps both are right. China’s SDR inclusion is not going to turn the world upside-down overnight. And if it was just the inclusion of one more currency in the global reserve basket (and only 10% of the basket at that), then this wouldn’t be significant all by itself. But while you were sleeping another development came along that gestures to the potentially transformative nature of this SDR makeover.

In August the World Bank announced to relatively little fanfare an historic bond issue: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IRBD), one of the five institutions under the World Bank umbrella, would sell nearly $3 billion worth of SDR-denominated bonds. And the currency of settlement? The Chinese yuan.

SDR-denominated bonds were flirted with decades ago, most recently in 1981, but the market for SDR bonds did not develop and they soon went the way of the dodo. But now, lo and behold, 35 years later they’re making a comeback, right in the heart of the world’s rising economic dragon.

SDR-denominated bonds were flirted with decades ago, most recently in 1981, but the market for SDR bonds did not develop and they soon went the way of the dodo. But now, lo and behold, 35 years later they’re making a comeback, right in the heart of the world’s rising economic dragon.

The issue, which went ahead on August 31st, serves a mundane, practical purpose: It allows Chinese investors to dabble in different currency assets without investing abroad. But at the same time it serves a much bigger purpose. In attempting to revive the long-dormant SDR bond market, China is tacitly backing the SDR as a reserve currency unto itself. Not a mere claim that is redeemed in other currencies by central banks in need of liquidity, but a settlement currency in and of itself.

As I explained before, this has been Beijing’s plan since the 2009 crisis: not to have the yuan replace the dollar as the global reserve, but to have the SDR replace the dollar. This allows the Chinese government to avoid having to liberalize the yuan or ease up on its rigid capital controls, but still gives it a seat at the table in a new global monetary order while simultaneously dethroning their best frenemy, the US. It’s win-win-win for China and, more importantly, win-win-win for the globalist oligarchs who want to bring in a New World Order of globally-administered currency.

As The Epoch Times puts it: “This is the first step toward one world currency.”

And guess what? It’s been in the planning for years, openly discussed in the central bankers’ white papers, decision documents and conferences, but conveniently unreported by the media and completely overlooked by the public.

And guess what? It’s been in the planning for years, openly discussed in the central bankers’ white papers, decision documents and conferences, but conveniently unreported by the media and completely overlooked by the public.

In March 2009, as the world was still reeling from the Global Financial Collapse, Zhou Xiaochuan, the Governor of the People’s Bank of China, published an essay on March 23, 2009 in an essay bluntly titled “Reform the international monetary system.” In it, he argued that the world could no longer afford to be tied to the US dollar and the vagaries of the American financial system. Instead, it needed to be presided over by those trustworthy angels at the IMF:

“Compared with separate management of reserves by individual countries, the centralized management of part of the global reserve by a trustworthy international institution with a reasonable return to encourage participation will be more effective in deterring speculation and stabilizing financial markets. The participating countries can also save some reserve for domestic development and economic growth. With its universal membership, its unique mandate of maintaining monetary and financial stability, and as an international ‘supervisor’ on the macroeconomic policies of its member countries, the IMF, equipped with its expertise, is endowed with a natural advantage to act as the manager of its member countries’ reserves.”

And in case that wasn’t clear enough, Zhou also wrote that: “The SDR has the features and potential to act as a super-sovereign reserve currency.”

The very next year the Bank for International Settlements (yes, that Bank for International Settlements), the European Central Bank and the World Bank jointly organized the Third Public Investors Conference, a chance for 80 central bankers, wealth fund and pension fund managers to hobnob at the BIS’ headquarters in Basel and discuss their world domination schemes. The results of that conference were collected in an edition of “BIS Papers” and published on the BIS website. One of those papers, penned by George Hoguet and Solomon Tadesse of State Street Global Advisors, discussed “The role of SDR-denominated securities in official and private portfolios” and predictably pimped the revival of SDR bonds that we are currently living through:

“An investor can synthetically replicate the weights of an SDR-denominated bond, but a security denominated in SDRs is self-rebalancing and is likely to minimize rebalancing costs. Additional research, particularly on the coordination problem (which limits liquidity) and operational issues, including settlement, can facilitate the development of an SDR-denominated bond market. Williamson (2009a) suggests that greater private use of the SDR could possibly facilitate greater official use, including the pegging of currencies to the SDR rather than to a basket of currencies or to some bilateral exchange rate.”

In other words, SDR bonds create the market for SDRs generally and legitimate their use as a settlement currency in their own right.

Now, six years later, here we are with the World Bank helping China issue SDR-denominated bonds. This is the real reason that this bond issue is happening at all. As The Epoch Times points out: “For the IBRD, there is no advantage because it is borrowing in strong currencies and getting paid in a relatively weak one.”

Now, six years later, here we are with the World Bank helping China issue SDR-denominated bonds. This is the real reason that this bond issue is happening at all. As The Epoch Times points out: “For the IBRD, there is no advantage because it is borrowing in strong currencies and getting paid in a relatively weak one.”

No, this is not about some wonderful new way for the World Bank to cheaply finance its bond issues; it is entirely about legitimizing the role of the SDR on the world stage as a potential world currency.

It remains to be seen whether this strategy will be successful. The first bond issue was a success, with a bid to cover ratio of 2.5 and 50 institutional investors—from central banks to domestic banks, brokerages and insurance companies—bidding on the instruments. But ZeroHedge quotes a fixed-income fund manager in Hong Kong who was not so impressed by the auction: “We are not interested in SDR bonds and we can’t see why Chinese investors should want these bonds since they can easily buy much higher yielding bonds in China.”

Whether SDR bonds will take off depends completely on whether the central bankers can convince the financial world of the benefits of scuttling the dollar reserve system. That will take some concerted effort, which is why we should expect to see an increase in stories raising awareness about SDRs and their potential utility in the coming years.

In that sense, the spate of stories this weekend about the yuan’s SDR inclusion may not be so much the end of the world as the first wave of propaganda getting people ready for the end of the world.